Shop Now

-

ACRYLIC PAINTS & MEDIUMS

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Featured

- Clearance

- ART SPECTRUM ACRYLIC MEDIUMS

- ART SPECTRUM COLOURFIX PRIMER

- ATELIER MEDIUMS

- AUREUO ACRYLIC PAINT SETS

- CHROMACRYL MEDIUMS

- CHROMACRYL STUDENT ACRYLIC

- DERIVAN MEDIUMS

- DERIVAN STUDENT ACRYLIC PAINT

- FLASHE

- FLUID WRITER PENS

- GOLDEN FLUID ACRYLIC

- GOLDEN HEAVY BODY ACRYLIC

- GOLDEN HIGH FLOW ACRYLIC

- GOLDEN MEDIUMS & VARNISHES

- GOLDEN OPEN ACRYLIC

- GOLDEN SOFLAT MATTE ACRYLIC

- MATISSE BACKGROUND

- MATISSE MEDIUMS

- MATISSE STRUCTURE

- NAM VARNISHES

- PEBEO ACRYLIC MEDIUMS

- PEBEO ORIGIN ACRYLIC

- PEBEO STUDIO ACRYLIC

- SCHMINCKE ACRYLIC MEDIUMS

- SCHMINCKE AEROCOLOR ACRYLIC

- SCHMINCKE AKADEMIE ACRYLIC

- SCHMINCKE PRIMACRYL PROFESSIONAL ACRYLIC

- WINSOR & NEWTON ACRYLIC MEDIUMS

- WINSOR & NEWTON ARTISTS ACRYLIC

- AIRBRUSHES

- ART ACCESSORIES

- ART BAGS, PORTFOLIOS & PRESENTATION

- BOARD & CARD

-

BOOKS

- New Arrivals

- BOOKS ACRYLIC PAINTING

- BOOKS ARCHITECTURE

- BOOKS ART AND CRAFT KITS

- BOOKS CHARACTER DESIGN

- BOOKS COLOUR THEORY

- BOOKS COLOURING BOOKS

- BOOKS CREATIVE KIDS

- BOOKS DRAWING

- BOOKS FASHION & TEXTILES

- BOOKS FIGURE DRAWING

- BOOKS FLORA AND FAUNA

- BOOKS GRAPHIC DESIGN

- BOOKS HAND LETTERING

- BOOKS ILLUSTRATION

- BOOKS KAWAII

- BOOKS LOGO DESIGN

- BOOKS MANGA

- BOOKS MIXED MEDIA

- BOOKS MONOGRAPHS

- BOOKS MOTIVATIONAL

- BOOKS NZ AOTEAROA ART

- BOOKS OIL PAINTING

- BOOKS ORIGAMI

- BOOKS PACKAGING DESIGN

- BOOKS PAPER ARTS

- BOOKS PHOTO TECHNIQUES

- BOOKS PHOTOGRAPHY

- BOOKS PRINTMAKING

- BOOKS PRODUCT DESIGN

- BOOKS PUZZLES AND GAMES

- BOOKS SCULPTURE AND CLAY

- BOOKS STREET ART

- BOOKS TYPOGRAPHY

- BOOKS URBAN SKETCHING

- BOOKS WATERCOLOUR PAINTING

-

BRUSHES & PALETTE KNIVES

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Clearance

- BAMBOO BRUSHES

- BRUSH SOAP & CLEANERS

- BRUSH STANDS & STORAGE

- COLOUR SHAPERS

- DA VINCI BLACK SABLE BRUSHES

- DA VINCI BRISTLE BRUSHES

- DA VINCI BRUSH SETS

-

DA VINCI CASANEO WATERCOLOUR BRUSH

- DA VINCI CASANEO FLAT BRUSH

- DA VINCI CASANEO LINER BRUSH

- DA VINCI CASANEO MINI BRUSHES

- DA VINCI CASANEO MOTTLER

- DA VINCI CASANEO OVAL BRUSH

- DA VINCI CASANEO POCKET TRAVEL BRUSH

- DA VINCI CASANEO RIGGER BRUSH

- DA VINCI CASANEO ROUND BRUSH

- DA VINCI CASANEO SHORT STROKE BRUSH

- DA VINCI CASANEO SLANT EDGE BRUSH

- DA VINCI CASANEO WASH BRUSH

- DA VINCI CHUNEO SYNTHETIC BRISTLE BRUSHES

- DA VINCI COLINEO OIL & ACRYLIC LONG HANDLED BRUSHES

-

DA VINCI COLINEO WATERCOLOUR BRUSHES

- DA VINCI COLINEO WATERCOLOUR BRUSH FAN

- DA VINCI COLINEO WATERCOLOUR BRUSH FLAT

- DA VINCI COLINEO WATERCOLOUR BRUSH RETOUCHING

- DA VINCI COLINEO WATERCOLOUR BRUSH RIGGER

- DA VINCI COLINEO WATERCOLOUR BRUSH ROUND

- DA VINCI COLINEO WATERCOLOUR BRUSH SLANTED

- DA VINCI COLINEO WATERCOLOUR BRUSH WASH

- DA VINCI COLINEO WATERCOLOUR BRUSH X POINT

- DA VINCI COSMOTOP MIX BRUSHES

- DA VINCI COSMOTOP NOVA BRUSHES

- DA VINCI COSMOTOP SPIN BRUSHES

- DA VINCI COSMOTOP WASH BRUSHES

- DA VINCI DRY BRUSHES SYNTHETIC

- DA VINCI FORTE BRUSHES

- DA VINCI IMPASTO BRUSHES

- DA VINCI JUNIOR SYNTHETIC BRUSHES

- DA VINCI KOLINSKY RED SABLE BRUSHES

- DA VINCI LETTERING BRUSHES

- DA VINCI MAESTRO2 BRISTLE BRUSHES

- DA VINCI MICRO BRUSHES

- DA VINCI PADDLE BRUSHES

- DA VINCI SPECIAL BRUSHES

- DA VINCI SQUIRREL/WASH BRUSHES

-

DA VINCI STUDENT BRUSHES

- DA VINCI COLLEGE BRUSH FILBERT

- DA VINCI COLLEGE BRUSH FLAT

- DA VINCI COLLEGE BRUSH ROUND

- DA VINCI FIT HOBBY BRUSH FILBERT

- DA VINCI FIT HOBBY BRUSH FLAT

- DA VINCI FIT HOBBY BRUSH ROUND

- DA VINCI FIT HOBBY SYNTHETIC MOTTLER BRUSH

- DA VINCI FIT SYNTHETIC BRISTLE BRUSH FLAT

- DA VINCI FIT SYNTHETIC BRISTLE BRUSH ROUND

- DA VINCI STUDENT BRISTLE ROUND

- DA VINCI TOP-ACRYL BRUSHES

- ESSDEE SPONGE ROLLERS

- EXPRESSION BRUSHES

- JASART 577 ETERNA BRUSH

- JASART HOG BRISTLE BRUSHES

- JASART MOP & STENCIL BRUSHES

- PALETTE KNIVES

- PEBEO BRUSH SETS

- PEBEO IRIS BRUSHES

- PEBEO MOTTLER BRUSHES

- WINSOR & NEWTON COTMAN WATERCOLOUR BRUSHES

- WINSOR & NEWTON GALERIA BRUSHES

- WINSOR & NEWTON SCEPTRE GOLD BRUSHES

- WINSOR & NEWTON SERIES 7 BRUSHES

- WINSOR & NEWTON WINTON BRUSHES

-

CANVAS & PANELS

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- CANVAS ROLLS

- CANVAS STRETCHING TOOLS

- CEDAR STRETCHER BARS

- EXPRESSION CANVAS PANELS

- EXPRESSION CRADLED GESSO BOARDS

- EXPRESSION FLOATING CANVAS FRAMED

- EXPRESSION STRETCHED CANVAS

- FREDRIX STRETCHED CANVAS, PANELS, PADS

- MUSEO LINEN CANVAS

- MUSEUM STRETCHED CANVAS

- NAM NATURAL LINEN CANVAS

- NAM ROUND CANVAS PANELS

- PINE STRETCHER BARS & BRACES

- PRO-PANELS

- SKATEBOARD DECK ART BOARD

- STRETCHED WITH LOVE CANVAS

- CERAMIC PAINT

- DRAWING BOARDS,STANDS & TABLES

- EASELS

- ENCAUSTIC PAINTS & MEDIUMS

- ENVELOPES

- FABRIC PAINT, DYES & ACCESSORIES

- FACE & BODY PAINT

- FOAMBOARD

- GIFT CARDS

- GLASS PAINT

- GOUACHE PAINTS

- INKS

-

KNIVES & CUTTING TOOLS

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Clearance

- DAFA CUTTING TOOLS

- DAFA RULERS

- DESIGN PEN KNIFE

- EXCEL KNIVES & CARVING TOOLS

- EXPRESSION CUTTING MATS

- FISKARS CUTTING TOOLS

- LEDAH TRIMMERS & GUILLOTINES

- LOGAN CUTTING & FRAMING TOOLS

- REVOLVING LEATHER PUNCH

- SCISSORS

- SNAP BLADE KNIVES & BLADES

- SWANN MORTON SCALPEL KNIVES & BLADES

- LIGHT PADS, LIGHTBOXES & LIGHTING

-

MARKERS & PENS

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Featured

- Clearance

- ARTLINE PENS

- AUREUO ALCOHOL TWIN TIP MARKER SETS

- CALLIGRAPHY PENS & NIBS

- CLASS PACKS MARKERS & PENS

- COPIC CIAO MARKERS

- COPIC CLASSIC MARKERS

- COPIC GASENFUDE BRUSH PENS

- COPIC MULTI LINERS

- COPIC REFILL INKS

- COPIC SKETCH MARKERS

- CORRECTION TAPES & PENS

- FABER CASTELL ALBRECHT DURER WATERCOLOUR MARKERS

- FABER CASTELL BLACK EDITION SHAKE & PAINT MARKER

- FABER CASTELL CONNECTOR PEN SETS

- FABER CASTELL GRIP PLUS BALL PENS

- FABER CASTELL PITT ARTIST DUAL MARKER

- FABER CASTELL PITT ARTIST PENS

- ICON PENS & MARKERS

- INDIGRAPH FOUNTAIN PENS

- LAMY PENS

- LEUCHTTURM 1917 DREHGRIFFEL BALLPOINT PENS

- MARKER WALLETS & STORAGE

- MOLOTOW BLACKLINER PIGMENT LINER PENS

- MOLOTOW BURNER MARKERS

- MOLOTOW CHALK MARKERS - REFILLABLE

- MOLOTOW DRIPSTICKS

- MOLOTOW EXCHANGE TIPS

- MOLOTOW GRAFX MASKING LIQUID

- MOLOTOW LIQUID CHROME MARKERS

- MOLOTOW MASTERPIECE PAINT MARKERS

- MOLOTOW ONE4ALL PAINT MARKERS

- MOLOTOW SKETCHER MARKERS

- PEBEO 4ARTIST OIL BASED PAINT MARKERS

- PEBEO COLOREX WATERCOLOUR INK MARKERS

- PENTEL PENS

- PILOT MR SERIES PENS

- PILOT PENS

- POSCA MARKERS

- ROTRING PENS

- SCHMINCKE AERO LINER EMPTY MARKERS

- SCHNEIDER

- SHARPIE

- SHARPIE CREATIVE MARKER SETS

- STAEDTLER COLOUR FIBRE TIP PEN

- STAEDTLER DESIGN JOURNEY MARKER SETS

- STAEDTLER LUMOCOLOR MARKERS

- STAEDTLER MARS MATIC TECH PENS

- STAEDTLER PIGMENT ARTS PEN

- STAEDTLER PIGMENT LINER

- STAEDTLER TEXTSURFER HIGHLIGHTERS

- STAEDTLER TRIPLUS FINELINERS

- STAEDTLER WRITING PENS

- TEXTA LIQUID CHALK MARKERS

- TOMBOW DUAL BRUSH PENS

- TOMBOW FUDENOSUKE PENS

- U-KNOCK XQ GEL PEN

- UNI PENS & MARKERS

- WINSOR & NEWTON BRUSH MARKERS

- WINSOR & NEWTON PROMARKERS

- ZIG PENS

-

MODELLING , SCULPTING, CLAY & RESIN

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Clearance

- 3D PRINTING FILAMENT

- BALSA & BASSWOOD

- CHAVANT MODELLING CLAY

- CLAY SHAPERS

- CLAYTOON NON-HARDENING MODELLING CLAY

- DAS MODELLING CLAY

- ESSDEE ALUMINIUM ROLLERS

- EXCEL MODELLING TOOLS

- EXPRESSION MODELLING TOOLS

- FIMO

- FIMO AIR-DRY MODELLING CLAY

- FIMO EFFECT

- FIMO KIDS

- FIMO LEATHER-EFFECT

- FIMO PROFESSIONAL

- FIMO TOOLS & ACCESSORIES

- GEDEO CLAY, RESIN & MOULDING

- HOT WIRE FOAM TOOLS

- JOVI AIR HARDENING CLAY

- K&S METALS

- KIWI UNDERGLAZE

- MACS MUD CLAYS

- MDF BOARD & PLYWOOD PANELS

- MILLIPUT EPOXY PUTTY

- MISCELLANEOUS MODELLING TOOLS

- MODELLING COMPOUNDS & PLASTER

- MODELLING WIRE

- NORSKI RESINS & ACCESSORIES

- PAL TIYA PREMIUM

- PEBEO FLUID PIGMENTS FOR RESINS

- PLASTALINA NON-HARDENING MODELLING CLAY

- PLASTIC SHEET PRODUCTS

- POP STICKS

- PROTOLINA NON-HARDENING MODELLING CLAY

- RGM SCULPTING TOOLS

- SCULPEY CLAYS

- SCULPEY LIQUID BAKEABLE CLAY

- SCULPEY PREMO CLAY

- SCULPEY SOUFFLE CLAY

- SCULPEY TOOLS & ACCESSORIES

- SCULPEY ULTIMATE DIY KITS

- WOODEN SHEETS & STICKS

-

OIL PAINTS & MEDIUMS

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Clearance

- ART SPECTRUM ARTIST OILS

- ART SPECTRUM OIL MEDIUMS

- CHROMA ARCHIVAL OIL MEDIUMS

- EXPRESSION WATERSOLUBLE OIL STICKS

- FIVE STAR OIL MEDIUMS

- GAMBLIN MEDIUMS

- MAIMERI CLASSICO OIL

- MICHAEL HARDING OILS

- OLD HOLLAND OIL COLOURS

- PEBEO OIL MEDIUMS

- PEBEO XL OIL

- R&F PIGMENT OIL PAINT STICKS

- SCHMINCKE ARTIST OIL FLAKE WHITE

- SCHMINCKE MUSSINI OIL

- SCHMINCKE NORMA BLUE WATER-MIXABLE OIL

- SCHMINCKE NORMA PROFESSIONAL OIL

- SCHMINCKE OIL MEDIUMS

- SHELLAC

- TMK SOLVENTS & SPIRITS

- WILLIAMSBURG OIL

- WINSOR & NEWTON ARTISAN WATER MIXABLE OILS

- WINSOR & NEWTON ARTISTS OILS

- WINSOR & NEWTON GRIFFIN ALKYD FAST DRYING OIL COLOUR

- WINSOR & NEWTON OIL MEDIUMS

- WINSOR & NEWTON WINTON OILS

- PACKAGING PRODUCTS

-

PADS, BLOCKS & PACKS

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Clearance

- ARCHES PADS & BLOCKS

- AWAGAMI WASHI PACKS

- BOCKINGFORD PADS

- CANSON PADS & BLOCKS

- CLAIREFONTAINE PASTELMAT PADS

- COLOURFIX PADS & PACKS

- FABRIANO PADS, PACKS & BLOCKS

- GORDON HARRIS PADS

- GRAPH PAPER PADS & SHEETS

- HAHNEMUHLE PADS, PACKS AND BLOCKS

- LANA FINE ART PAPER PADS & PACKS

- MAGNANI BLOCKS & PADS

- MOLOTOW MARKER PADS

- WARWICK EXERCISE BOOKS & PADS

- WINSOR & NEWTON MARKER PADS

- X-PRESS IT BLENDING PADS

- PANTONE GUIDES

- PAPER & CARD COLOURED

- PAPER ACCESSORIES

-

PAPER FINE ART

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Clearance

- ARCHES FINE ART PAPERS

- AWAGAMI FINE ART PAPERS

- CANSON MI-TEINTES PAPER

- CANSON WATERCOLOUR PAPERS

- CARTRIDGE PAPER

- COLOURFIX PAPER

- EXPRESSION RENDERING PAPER

- FABRIANO FINE ART PAPERS

- GLASSINE PAPER

- HAHNEMUHLE FINE ART PAPER - ROLLS

- HAHNEMUHLE FINE ART PAPER - SHEETS

- KHADI PRINTMAKING PAPER

- LANA FINE ART PAPERS

- MAGNANI FINE ART PAPERS

- NEWSPRINT PAPER

- SCHOOL ART PAPER & CARD

- YUPO SYNTHETIC PAPER

-

PASTELS & PASTEL PENCILS

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Clearance

- CARAN D'ACHE NEOPASTEL

- CRETACOLOR PASTEL STICKS

- DERWENT PASTEL PENCIL SETS

- FABER CASTELL PITT PASTEL PENCILS

- FABER CASTELL POLYCHROMOS PASTELS

- HARD & SOFT PASTELS

- MUNGYO OIL PASTELS

- MUNGYO SEMI-HARD PASTELS

- MUNGYO SOFT PASTELS

- OIL PASTELS

- PAN PASTELS

- PASTEL FIXATIVES & GROUNDS

- SCHMINCKE PASTELS

- STAEDTLER DESIGN JOURNEY PASTEL & CRAYON SETS

-

PENCILS, CRAYONS, CHARCOAL & ACCESSORIES

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Featured

- Clearance

- ART GRAF GRAPHITE & CARBON

- BLACKWING

- CARAN D'ACHE LUMINANCE SETS

- CARAN D'ACHE NEOCOLOR I

- CARAN D'ACHE PABLO

- CARAN D'ACHE SUPRACOLOUR

- CHALK & ACCESSORIES

- CLASS PACKS PENCILS

- CLUTCH PENCILS, LEAD HOLDERS & LEADS

- COATES WILLOW CHARCOAL

- CONTE CRAYONS

- CRETACOLOR ARTISTS' COLOUR PENCILS

- CRETACOLOR CHARCOAL & GRAPHITE

- CRETACOLOR DRAWING & COLOUR PENCIL SETS

- Caran D'Ache NEOCOLOR CRAYONS

- DERWENT INKTENSE SINGLE PENCIL

- DERWENT SETS

- DONGXU WILLOW CHARCOAL STICKS

- DRAWING ACCESSORIES

- ERASERS

- EXPRESSION PAPER STUMPS

- FABER CASTELL 9000 PENCILS

- FABER CASTELL ALBRECHT DURER WATERCOLOUR PENCILS

- FABER CASTELL ARTISTS PENCILS

- FABER CASTELL GOLDFABER 1221 PENCILS

- FABER CASTELL PITT CHARCOAL & GRAPHITE

- FABER CASTELL PITT PASTEL STICKS

- FABER CASTELL POLYCHROMOS ARTISTS COLOUR PENCILS

- FABER CASTELL RED RANGE CLASSIC PENCIL SETS

- FABER CASTELL UNIVERSAL MARKING PENCILS

- GENERALS CHARCOAL PENCILS

- ICON PENCILS

- JOLLY X-BIG SUPERSTICK PENCILS

- LAMY COLOUR PENCIL SETS

- MECHANICAL PENCILS

- MOLESKINE PENCILS

- MUNGYO WATERCOLOUR CRAYONS

- PENCIL CASES & WRAPS

- PRISMACOLOR PENCILS

- SHARPENERS

- STAEDTLER COLOUR PENCIL SETS

- STAEDTLER CRAYON & PASTEL SETS

- STAEDTLER DESIGN JOURNEY COLOUR PENCIL SETS

- STAEDTLER LUMOCOLOR PENCILS

- STAEDTLER LUNA PENCILS

- STAEDTLER MARS LEADS

- STAEDTLER MARS LUMOGRAPH PENCILS

- STAEDTLER NORIS,NORICA PENCILS

- STAEDTLER TRADITION PENCILS

- TOMBOW MONO GRAPHITE PENCILS

- WOLFF CARBON PENCILS

- PIGMENTS & MEDIUMS

- PRINTER PAPERS, FILMS & LABELS

-

PRINTMAKING

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Clearance

- BLOCK PRINTING KITS

- CHARBONNEL ETCHING GROUNDS

- ESSDEE SCRAPERBOARD

- GELLI PRINTING PLATES

- JACQUARD CYANOTYPE

- JACQUARD SOLARFAST

- PRINTING PLATES, BLOCKS & LINO

- PRINTING PRESSES

-

PRINTMAKING INKS

- AKUA INTAGLIO INK

- AKUA INTAGLIO MEDIUMS

- CHARBONNEL ETCHING INKS

- CHARBONNEL WATER WASHABLE INK

- CHARBONNEL WATER WASHABLE MEDIUMS

- CRANFIELD CALIGO SAFE WASH ETCHING INKS

- CRANFIELD CALIGO SAFE WASH RELIEF INK

- CRANFIELD PRINTMAKING MEDIUMS

- CRANFIELD TRADITIONAL ETCHING INKS

- CRANFIELD TRADITIONAL RELIEF INKS

- ESSDEE FABRIC PRINTING INKS

- ESSDEE WATERBASED BLOCK PRINTING INKS

- FIVE STAR PRINTING INK

- FLINT OIL BASED PRINTING INK

- FLINT WATER BASED PRINTING INK

- SCHMINCKE AQUA LINOPRINT INKS

- SCHMINCKE LINOPRINT MEDIUMS

- SCHMINCKE LINOPRINT SETS

- SPEEDBALL FABRIC RELIEF INKS

- SPEEDBALL PROFESSIONAL RELIEF INKS

- SPEEDBALL WATERBASED RELIEF INKS

-

PRINTMAKING ROLLERS, CUTTERS & TOOLS

- BARENS

- BENCH HOOKS

- ESSDEE COLD WAX ROLLERS

- ESSDEE FABRIC INK ROLLERS

- ESSDEE HARD RUBBER INK ROLLERS

- ESSDEE PROFESSIONAL INK ROLLERS

- ESSDEE SOFT RUBBER INK ROLLERS

- ETCHING NEEDLES

- EXPRESSION STANDARD RUBBER INK ROLLERS

- HWAHONG ROLLERS & TOOLS

- LINO & WOOD CUTTERS & CARVING TOOLS

- SPEEDBALL LINO ROLLERS

- PRINTMAKING STENCILS

- PROJECTORS

- SCHOOL & UNIVERSITY KITS

- SCREENPRINTING

-

SKETCH BOOKS, NOTEBOOKS, VISUAL DIARIES

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Clearance

- CRESCENT RENDR SKETCHBOOKS

- FABRIANO ECOQUA NOTEBOOKS

- FABRIANO ISPIRA NOTEBOOKS

- FABRIANO SKETCH & WATERCOLOUR BOOKS

- FLEXBOOK SKETCHBOOKS & NOTEBOOKS

- GORDON HARRIS VISUAL DIARIES

-

HAHNEMUHLE SKETCH BOOKS

- HAHNEMUHLE CAPPUCINO BOOK

- HAHNEMUHLE DIARYFLEX BOOKS

- HAHNEMUHLE NOSTALGIE SKETCH BOOK

- HAHNEMUHLE SKETCH BOOK D&S

- HAHNEMUHLE SKETCH BOOK HARDCOVER

- HAHNEMUHLE SKETCH BOOKLETS

- HAHNEMUHLE SPIRAL BOUND SKETCH BOOKS

- HAHNEMUHLE THE GREY BOOK

- HAHNEMUHLE TONED WATERCOLOUR BOOKS

- HAHNEMUHLE TRAVEL JOURNALS

- HAHNEMUHLE WATERCOLOUR BOOKS

- HAHNEMUHLE ZIG ZAG BOOK

- LEUCHTTURM 1917 NOTEBOOKS

- MOLESKINE NOTEBOOKS

- MOLOTOW MARKER SKETCHBOOK

- PAPERBLANKS NOTEBOOKS

- SPECIALTY PAINTS & FINISHES

- SPRAY PAINT

- STATIONERY

-

TAPES, GLUES & ADHESIVES

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Clearance

- ADHESIVE PUTTIES & CEMENTS

- ARTOGRAPH SPRAY BOOTHS

- CELLULOSE & INVISIBLE TAPES

- DOUBLE SIDED TAPES & SHEETS

- GLUE GUNS & STICKS

- GLUE STICKS & ROLLERS

- HOLDFAST HOOK & LOOP

- MASKING TAPES & FILMS

- PACKAGING TAPE

- PAPER & CLOTH TAPES

- PVA & WOOD GLUES

- SELF ADHESIVE SHEETS & ROLLS

- SPECIALITY & ALL PURPOSE GLUES

- SPRAY ADHESIVES

- XYRON PROFESSIONAL

- TECHNICAL DRAWING PRODUCTS

- TRACING PAPER & DRAFTING FILM

-

WATERCOLOUR PAINTS & MEDIUMS

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Clearance

- DANIEL SMITH WATERCOLOUR

- PEBEO WATERCOLOUR MEDIUMS

- PEBEO WATERCOLOUR PAINT SETS

- QOR WATERCOLOURS

- SCHMINCKE AKADEMIE WATERCOLOUR

- SCHMINCKE AQUA DROP

- SCHMINCKE HORADAM WATERCOLOUR

- SCHMINCKE LIQUID CHARCOAL

- SCHMINCKE WATERCOLOUR MEDIUMS

- WATERBRUSH PENS

- WATERCOLOUR STUDENT PAINT SETS

- WINSOR & NEWTON COTMAN WATERCOLOURS

- WINSOR & NEWTON PROFESSIONAL WATERCOLOUR

- WINSOR & NEWTON WATERCOLOUR MARKERS

- WINSOR & NEWTON WATERCOLOUR MEDIUMS

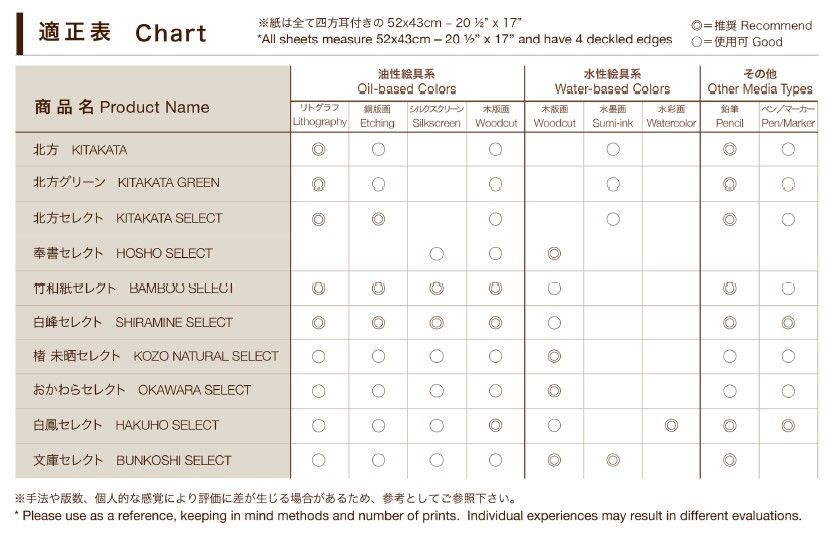

NEW Awagami washi paper range

Awagami produces washi from natural fibers: Kozo, Bamboo, Mitsumata, Gampi and Hemp to create papers for Fine Art, Inkjet Printing, Crafts, Interior Design and Art Conservation. Awagami also collaborates with international artisans to explore new concepts that may prove suitable for washi papermaking.

Washi and the Environment

Since antiquity, Japanese washi has been made from renewable plant resources that reach maturity in 1-2 years. When compared to wood-based papers (that take dozens of years to mature and require many chemicals), washi is created with significantly less harm to our environment in a clean and eco-friendly manner. In the traditional spirit of Japan, Awagami papermaking maintains a caring and nurturing focus on the environment.

Awagami Washi and the Fujimori Family

6th generation, Minoru Fujimori took over the family business in 1945 determined to continue washi papermaking despite post-WWII difficulties. In 1970, Minoru-san was designated as an ‘Intangible Cultural Property of Tokushima’ in recognition of his skills. In 1976, Awagami washi was designated as a ‘Traditional Craft Industry’ and in 1986, Minoru Fujimori was further honored as Master Craftsman and awarded the ‘Sixth Class Order of Merit, Sacred Treasure’ by the Emperor.

Currently his son, Yoichi and family continue the papermaking tradition as their ancestors did before. In 2022, Yoichi-san became the second Awagami papermaker bestowed by the Emperor with the honorific of 'Order of the Sacred Treasure, Silver Rays'; a tremendous family accomplishment, indeed. In an effort to preserve the craft and pass washi papermaking onto the next generation, the family has established a network of international partners that offer Awagami papers to worldwide artists.

Washi Paper Basics

Awagami washi papers are 100% solely made in Tokushima Japan. In order to keep up with international demand the mill makes both handmade and machine made papers. “Tamezuki“ and “Nagashizuki” are the two handmade methods employed; with Tamezuki being the older of the two methods.

Tamezuki - Papermaking in the ancient Heien period was described as follows: pulps such as kozo (mulberry), hemp and gampi were cut into small pieces and cooked in a mild alkaline solution. The cooked material was rinsed, cleaned and beaten to break down the fibers. The resulting pulp was then mixed with water and scooped onto a screened frame. Prior to any water drain, the papermaker gently shook the frame or ‘mould’ to even out the pulp distribution. The paper was formed by a single scoop in the vat. Newly formed sheets of paper were stacked on top of each other; separated by cloth to prevent them from sticking together. This method is similar to papermaking in the West.

Early Japanese papermakers astutely noticed that pulp containing gampi fibers had a slower drainage rate allowing the papermakers to repeatedly move the pulp mixture back and forth over the mould’s surface resulting in a stronger paper (with more evenly intertwined fibers). It was subsequently discovered that gampi releases a viscous liquid that actually changes the viscosity of the water resulting in this slower drainage rate. For some time, gampi fibers were added to other fibers to achieve this effect but since gampi is not cultivatable, it was difficult to obtain significant quantities. The key viscous material or “neri” was then extracted from other more readily available plants leading to the development of the “Nagashizuki” style of papermaking which yields the strong, thin and semi-translucent papers that has become synonymous with washi.

Harvesting & Processing the Kozo Fibre

Kozo fiber grows on the mountainside adjacent to the mill. The stalks are steamed for bark removal and hung out in bunches to dry. The soaked bark is carefully stepped upon and rubbed between the feet in running water to remove the loosened dark outer bark. Once the dark outer layer is removed, the ‘Aohada’ green layer is carefully scraped away with a knife. The amount of this Aohada removed determines the natural whiteness of the final paper. The cleaned “SHIROKAWA” or white bark is dried in a cool shaded area until ready for further processing.

The prepared bark is then cooked in an alkaline solution such as wood ash (or potash), caustic soda, or soda ash. The characteristic feel of washi is determined by the amount of non-cellulose materials contained in the fibers which are broken down in the cooking process. When a strong alkali is used, more of the non-cellulose materials are dissolved thus resulting in a softer paper. If more non-cellulose materials remain in the fiber, then the paper has more body. The following day, the cooked bark is removed and thoroughly rinsed in running water until there are no traces of the dark alkaline solution. If white paper is to be made, the fibers are bleached at this stage. Traditionally, natural bleaching methods involving running water, sunlight and snow were used. Nowadays various eco-friendly bleaching agents can also be used. The fibres are cleaned again and any scar tissue, buds, discolored areas etc. are carefully removed. The cleaned strips of damp fiber are now ready for beating on a wooden or stone surface. The separate strips are beaten until they become a mass of separated fibers. Today, beating is also done using automated ‘NAGINATA’ beaters. The beating process separates and roughens the surface of the fibers.

Basic Papermaking Tools

The fundamental tools required to create Japanese and Western papers are basically the same. The vat or ‘SUKIBUNE’ is traditionally made from pine or cypress with contemporary versions lined in stainless steel. The primary function of the sukibune is to hold the fiber-neri-water mixture but it has several attachments making it different from a Western vat. On the left/right side are two notched posts or ‘TORII’ supporting the ‘UMAGUWA’ (a large comb-like tool) used to mix the fibers in the vat. Inside the sukibune are two narrow boards or ‘OTTORI’ used to rest or support the ‘KETA’ (papermaking mould) when opening it to remove/insert the ‘SU’ (flexible screen). The major difference between Japanese and Western moulds is Western moulds have a removable deckle with an attached rigid screen while Japanese mould and deckles are actually hinged together with a flexible/removable screen.

Basic Papermaking Process

The beaten fiber is added to water in the sukibune. Neri solution is then added (the amount depends on the type of paper to be made). The Nagashizuki method requires the fiber mixture to be in constant motion over the surface of the screen. The actual motion involved varies according to the kind of fiber used, paper to be made and the individual papermaker. The screen and the completed sheet of paper are removed from the keta and in a smooth overhead motion from mould to the ‘SHITODAI’ or couching stand. When the entire screen with new sheet is laid on the post, the screen may be lifted. It’s carefully peeled off away from the papermaker and replaced in the mould.

The post of newly made papers is lightly weighted and allowed to drain naturally overnight. The next day, it is put into the ‘ASAKUKI’ or press and gradually pressed until 30% of the moisture is removed. The pressed papers are carefully removed one-by-one and brushed onto boards to dry naturally or onto a steam heated metal surface for quicker drying. The drying method, be it natural or mechanical, significantly affects the finished paper, so the drying is always matched with the particular type of paper being made.