Shop Now

-

ACRYLIC PAINTS & MEDIUMS

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Featured

- Clearance

- ART SPECTRUM ACRYLIC MEDIUMS

- ART SPECTRUM COLOURFIX PRIMER

- ATELIER MEDIUMS

- AUREUO ACRYLIC PAINT SETS

- CHROMACRYL MEDIUMS

- CHROMACRYL STUDENT ACRYLIC

- DERIVAN MEDIUMS

- DERIVAN STUDENT ACRYLIC PAINT

- EXPRESSION PAINTING SETS

- FLASHE

- FLUID WRITER PENS

- GOLDEN FLUID ACRYLIC

- GOLDEN HEAVY BODY ACRYLIC

- GOLDEN HIGH FLOW ACRYLIC

- GOLDEN MEDIUMS & VARNISHES

- GOLDEN OPEN ACRYLIC

- GOLDEN SOFLAT MATTE ACRYLIC

- MATISSE BACKGROUND

- MATISSE MEDIUMS

- MATISSE STRUCTURE

- NAM VARNISHES

- PEBEO ACRYLIC MEDIUMS

- PEBEO ORIGIN ACRYLIC

- PEBEO STUDIO ACRYLIC

- SCHMINCKE ACRYLIC MEDIUMS

- SCHMINCKE AEROCOLOR ACRYLIC

- SCHMINCKE AKADEMIE ACRYLIC

- WINSOR & NEWTON ACRYLIC MEDIUMS

- WINSOR & NEWTON ARTISTS ACRYLIC

- AIRBRUSHES

- ART ACCESSORIES

- ART BAGS, PORTFOLIOS & PRESENTATION

- BOARD & CARD

-

BOOKS

- New Arrivals

- BOOKS ACRYLIC PAINTING

- BOOKS ARCHITECTURE

- BOOKS ART AND CRAFT KITS

- BOOKS CHARACTER DESIGN

- BOOKS COLOUR THEORY

- BOOKS COLOURING BOOKS

- BOOKS CREATIVE KIDS

- BOOKS DRAWING

- BOOKS FASHION & TEXTILES

- BOOKS FIGURE DRAWING

- BOOKS FLORA AND FAUNA

- BOOKS GRAPHIC DESIGN

- BOOKS HAND LETTERING

- BOOKS ILLUSTRATION

- BOOKS KAWAII

- BOOKS LOGO DESIGN

- BOOKS MANGA

- BOOKS MIXED MEDIA

- BOOKS MONOGRAPHS

- BOOKS MOTIVATIONAL

- BOOKS NZ AOTEAROA ART

- BOOKS OIL PAINTING

- BOOKS ORIGAMI

- BOOKS PACKAGING DESIGN

- BOOKS PAPER ARTS

- BOOKS PHOTO TECHNIQUES

- BOOKS PHOTOGRAPHY

- BOOKS PRINTMAKING

- BOOKS PRODUCT DESIGN

- BOOKS PUZZLES AND GAMES

- BOOKS SCULPTURE AND CLAY

- BOOKS STREET ART

- BOOKS TYPOGRAPHY

- BOOKS URBAN SKETCHING

- BOOKS WATERCOLOUR PAINTING

-

BRUSHES & PALETTE KNIVES

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Featured

- Clearance

- BAMBOO BRUSHES

- BRUSH SOAP & CLEANERS

- BRUSH STANDS & STORAGE

- COLOUR SHAPERS

- DA VINCI BLACK SABLE BRUSHES

- DA VINCI BRISTLE BRUSHES

- DA VINCI BRUSH SETS

-

DA VINCI CASANEO WATERCOLOUR BRUSH

- DA VINCI CASANEO FLAT BRUSH

- DA VINCI CASANEO LINER BRUSH

- DA VINCI CASANEO MINI BRUSHES

- DA VINCI CASANEO MOTTLER

- DA VINCI CASANEO OVAL BRUSH

- DA VINCI CASANEO POCKET TRAVEL BRUSH

- DA VINCI CASANEO RIGGER BRUSH

- DA VINCI CASANEO ROUND BRUSH

- DA VINCI CASANEO SHORT STROKE BRUSH

- DA VINCI CASANEO SLANT EDGE BRUSH

- DA VINCI CASANEO WASH BRUSH

- DA VINCI CHUNEO SYNTHETIC BRISTLE BRUSHES

- DA VINCI COLINEO OIL & ACRYLIC LONG HANDLED BRUSHES

- DA VINCI COLINEO WATERCOLOUR BRUSHES

- DA VINCI COSMOTOP MIX BRUSHES

- DA VINCI COSMOTOP NOVA BRUSHES

- DA VINCI COSMOTOP SPIN BRUSHES

- DA VINCI COSMOTOP WASH BRUSHES

- DA VINCI DRY BRUSHES SYNTHETIC

- DA VINCI FORTE BRUSHES

- DA VINCI IMPASTO BRUSHES

- DA VINCI JUNIOR SYNTHETIC BRUSHES

-

DA VINCI KOLINSKY RED SABLE BRUSHES

- DA VINCI ARTIST COLLECTION GRIS BRUSH

- DA VINCI KOLINSKY SABLE WATERCOLOUR BRUSH SERIES 36

- DA VINCI LETTERING BRUSH POINT

- DA VINCI MAESTRO KOLINSKY SABLE WATERCOLOUR BRUSH SERIES 11

- DA VINCI MAESTRO KOLINSKY SABLE WATERCOLOUR BRUSH SERIES 35

- DA VINCI MAESTRO MINIATURE BRUSHES

- DA VINCI RED SABLE POCKET TRAVEL BRUSH

- DA VINCI LETTERING BRUSHES

- DA VINCI MAESTRO2 BRISTLE BRUSHES

- DA VINCI MICRO BRUSHES

- DA VINCI SPECIAL BRUSHES

- DA VINCI SQUIRREL/WASH BRUSHES

- DA VINCI STUDENT BRUSHES

- DA VINCI TOP-ACRYL BRUSHES

- ESSDEE SPONGE ROLLERS

- EXPRESSION BRUSHES

- JASART 577 ETERNA BRUSH

- JASART HOG BRISTLE BRUSHES

- JASART MOP & STENCIL BRUSHES

- PALETTE KNIVES

- PEBEO BRUSH SETS

- PEBEO IRIS BRUSHES

- PEBEO MOTTLER BRUSHES

- WINSOR & NEWTON COTMAN WATERCOLOUR BRUSHES

- WINSOR & NEWTON GALERIA BRUSHES

- WINSOR & NEWTON SCEPTRE GOLD BRUSHES

- WINSOR & NEWTON SERIES 7 BRUSHES

- WINSOR & NEWTON WINTON BRUSHES

-

CANVAS & PANELS

- Specials

- CANVAS ROLLS

- CANVAS STRETCHING TOOLS

- CEDAR STRETCHER BARS

- EXPRESSION CANVAS PANELS

- EXPRESSION FLOATING CANVAS FRAMED

- EXPRESSION STRETCHED CANVAS

- FREDRIX STRETCHED CANVAS, PANELS, PADS

- MUSEO LINEN CANVAS

- MUSEUM STRETCHED CANVAS

- NAM NATURAL LINEN CANVAS

- NAM ROUND CANVAS PANELS

- PINE STRETCHER BARS & BRACES

- PRO-PANELS

- SKATEBOARD DECK ART BOARD

- STRETCHED WITH LOVE CANVAS

- CERAMIC PAINT

- DRAWING BOARDS,STANDS & TABLES

- EASELS

- ENCAUSTIC PAINTS & MEDIUMS

- ENVELOPES

- FABRIC PAINT & DYES

- FACE & BODY PAINT

- FOAMBOARD

- GIFT CARDS

- GLASS PAINT

- GOUACHE PAINTS

- INKS

-

KNIVES & CUTTING TOOLS

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Featured

- Clearance

- DAFA CUTTING TOOLS

- DAFA RULERS

- DESIGN PEN KNIFE

- EXCEL KNIVES & CARVING TOOLS

- EXPRESSION CUTTING MATS

- FISKARS CUTTING TOOLS

- LEDAH TRIMMERS & GUILLOTINES

- LOGAN CUTTING & FRAMING TOOLS

- REVOLVING LEATHER PUNCH

- SCISSORS

- SNAP BLADE KNIVES & BLADES

- SWANN MORTON SCALPEL KNIVES & BLADES

- LIGHT PADS, LIGHTBOXES & LIGHTING

-

MARKERS & PENS

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Featured

- Clearance

- ARTLINE PENS

- AUREUO ALCOHOL TWIN TIP MARKER SETS

- CALLIGRAPHY PENS & NIBS

- CLASS PACKS MARKERS & PENS

- COPIC CIAO MARKERS

- COPIC CLASSIC MARKERS

- COPIC GASENFUDE BRUSH PENS

- COPIC MULTI LINERS

- COPIC REFILL INKS

- COPIC SKETCH MARKERS

- CORRECTION TAPES & PENS

- FABER CASTELL ALBRECHT DURER WATERCOLOUR MARKERS

- FABER CASTELL CONNECTOR PEN SETS

- FABER CASTELL GRIP PLUS BALL PENS

- FABER CASTELL PITT ARTIST DUAL MARKER

- FABER CASTELL PITT ARTIST PENS

- ICON PENS & MARKERS

- INDIGRAPH FOUNTAIN PENS

- LAMY PENS

- MARKER WALLETS & STORAGE

- MOLOTOW BLACKLINER PIGMENT LINER PENS

- MOLOTOW BURNER MARKERS

- MOLOTOW CHALK MARKERS - REFILLABLE

- MOLOTOW DRIPSTICKS

- MOLOTOW EXCHANGE TIPS

- MOLOTOW GRAFX MASKING LIQUID

- MOLOTOW LIQUID CHROME MARKERS

- MOLOTOW MASTERPIECE PAINT MARKERS

- MOLOTOW ONE4ALL PAINT MARKERS

- MOLOTOW SKETCHER MARKERS

- PEBEO 4ARTIST OIL BASED PAINT MARKERS

- PEBEO COLOREX WATERCOLOUR INK MARKERS

- PENTEL PENS

- PILOT MR SERIES PENS

- PILOT PENS

- POSCA MARKERS

- ROTRING PENS

- SCHMINCKE AERO LINER EMPTY MARKERS

- SCHNEIDER

- SHARPIE

- SHARPIE CREATIVE MARKER SETS

- STABILO FINELINER PENS

- STAEDTLER COLOUR FIBRE TIP PEN

- STAEDTLER DESIGN JOURNEY MARKER SETS

- STAEDTLER LUMOCOLOR MARKERS

- STAEDTLER MARS MATIC TECH PENS

- STAEDTLER PIGMENT ARTS PEN

- STAEDTLER PIGMENT LINER

- STAEDTLER TEXTSURFER HIGHLIGHTERS

- STAEDTLER TRIPLUS FINELINERS

- STAEDTLER WRITING PENS

- TEXTA LIQUID CHALK MARKERS

- TOMBOW DUAL BRUSH PENS

- TOMBOW FUDENOSUKE PENS

- U-KNOCK XQ GEL PEN

- UNI PENS & MARKERS

- WINSOR & NEWTON BRUSH MARKERS

- WINSOR & NEWTON PROMARKERS

- ZIG PENS

-

MODELLING , SCULPTING, CLAY & RESIN

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Featured

- Clearance

- 3D PRINTING FILAMENT

- BALSA & BASSWOOD

- CHAVANT MODELLING CLAY

- CLAY SHAPERS

- CLAYTOON NON-HARDENING MODELLING CLAY

- DAS MODELLING CLAY

- ESSDEE ALUMINIUM ROLLERS

- EXCEL MODELLING TOOLS

- EXPRESSION MODELLING TOOLS

- FIMO

- FIMO AIR-DRY MODELLING CLAY

- FIMO EFFECT

- FIMO KIDS

- FIMO LEATHER-EFFECT

- FIMO PROFESSIONAL

- FIMO TOOLS & ACCESSORIES

- GEDEO CLAY, RESIN & MOULDING

- HOT WIRE FOAM TOOLS

- JOVI AIR HARDENING CLAY

- K&S METALS

- KIWI UNDERGLAZE

- MACS MUD CLAYS

- MDF BOARD & PLYWOOD PANELS

- MILLIPUT EPOXY PUTTY

- MISCELLANEOUS MODELLING TOOLS

- MODELLING COMPOUNDS & PLASTER

- MODELLING WIRE

- NORSKI RESINS & ACCESSORIES

- PEBEO FLUID PIGMENTS FOR RESINS

- PLASTALINA NON-HARDENING MODELLING CLAY

- PLASTIC SHEET PRODUCTS

- POP STICKS

- PROTOLINA NON-HARDENING MODELLING CLAY

- RGM SCULPTING TOOLS

- SCULPEY CLAYS

- SCULPEY LIQUID BAKEABLE CLAY

- SCULPEY PREMO CLAY

- SCULPEY SOUFFLE CLAY

- SCULPEY TOOLS & ACCESSORIES

- WOODEN SHEETS & STICKS

-

OIL PAINTS & MEDIUMS

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Clearance

- ART SPECTRUM ARTIST OILS

- ART SPECTRUM OIL MEDIUMS

- CHROMA ARCHIVAL OIL MEDIUMS

- EXPRESSION WATERSOLUBLE OIL STICKS

- FIVE STAR OIL MEDIUMS

- GAMBLIN MEDIUMS

- MAIMERI CLASSICO OIL

- MICHAEL HARDING OILS

- OLD HOLLAND OIL COLOURS

- PEBEO OIL MEDIUMS

- PEBEO XL OIL

- R&F PIGMENT OIL PAINT STICKS

- SCHMINCKE ARTIST OIL FLAKE WHITE

- SCHMINCKE MUSSINI OIL

- SCHMINCKE NORMA BLUE WATER-MIXABLE OIL

- SCHMINCKE NORMA PROFESSIONAL OIL

- SCHMINCKE OIL MEDIUMS

- SHELLAC

- TMK SOLVENTS & SPIRITS

- WILLIAMSBURG OIL

- WINSOR & NEWTON ARTISAN WATER MIXABLE OILS

- WINSOR & NEWTON ARTISTS OILS

- WINSOR & NEWTON GRIFFIN ALKYD FAST DRYING OIL COLOUR

- WINSOR & NEWTON OIL MEDIUMS

- WINSOR & NEWTON WINTON OILS

- PACKAGING PRODUCTS

-

PADS, BLOCKS & PACKS

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Clearance

- ARCHES PADS & BLOCKS

- AWAGAMI WASHI PACKS

- BOCKINGFORD PADS

- CANSON PADS & BLOCKS

- CLAIREFONTAINE PASTELMAT PADS

- COLOURFIX PADS & PACKS

- FABRIANO PADS, PACKS & BLOCKS

- GORDON HARRIS PADS

- GRAPH PAPER PADS & SHEETS

- HAHNEMUHLE PADS, PACKS AND BLOCKS

- LANA FINE ART PAPER PADS

- MAGNANI BLOCKS & PADS

- MOLOTOW MARKER PADS

- WARWICK EXERCISE BOOKS & PADS

- WINSOR & NEWTON MARKER PADS

- X-PRESS IT BLENDING PADS

- PANTONE GUIDES

- PAPER & CARD COLOURED

- PAPER ACCESSORIES

-

PAPER FINE ART

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Clearance

- ARCHES FINE ART PAPERS

- AWAGAMI FINE ART PAPERS

- CANSON MI-TEINTES PAPER

- CANSON WATERCOLOUR PAPERS

- CARTRIDGE PAPER

- COLOURFIX PAPER

- EXPRESSION RENDERING PAPER

- FABRIANO FINE ART PAPERS

- GLASSINE PAPER

- HAHNEMUHLE FINE ART PAPER - ROLLS

- HAHNEMUHLE FINE ART PAPER - SHEETS

- KHADI PRINTMAKING PAPER

- LANA FINE ART PAPERS

- MAGNANI FINE ART PAPERS

- NEWSPRINT PAPER

- SCHOOL ART PAPER & CARD

- YUPO SYNTHETIC PAPER

-

PASTELS & PASTEL PENCILS

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Featured

- Clearance

- CARAN D'ACHE NEOPASTEL

- CRETACOLOR PASTEL STICKS

- DERWENT PASTEL PENCIL SETS

- FABER CASTELL PITT PASTEL PENCILS

- FABER CASTELL POLYCHROMOS PASTELS

- HARD & SOFT PASTELS

- MUNGYO OIL PASTELS

- MUNGYO SEMI-HARD PASTELS

- MUNGYO SOFT PASTELS

- NAM VARNISHES

- OIL PASTELS

- PAN PASTELS

- PASTEL FIXATIVES & GROUNDS

- SCHMINCKE PASTELS

- STAEDTLER DESIGN JOURNEY PASTEL & CRAYON SETS

-

PENCILS, CRAYONS, CHARCOAL & ACCESSORIES

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Clearance

- ART GRAF GRAPHITE & CARBON

- BLACKWING

- CARAN D'ACHE LUMINANCE SETS

- CARAN D'ACHE NEOCOLOR I

- CARAN D'ACHE PABLO

- CARAN D'ACHE SUPRACOLOUR

- CHALK & ACCESSORIES

- CLASS PACKS PENCILS

- CLUTCH PENCILS, LEAD HOLDERS & LEADS

- COATES WILLOW CHARCOAL

- CONTE CRAYONS

- CRETACOLOR ARTISTS' COLOUR PENCILS

- CRETACOLOR CHARCOAL & GRAPHITE

- CRETACOLOR DRAWING & COLOUR PENCIL SETS

- Caran D'Ache NEOCOLOR CRAYONS

- DERWENT INKTENSE SINGLE PENCIL

- DERWENT SETS

- DONGXU WILLOW CHARCOAL STICKS

- DRAWING ACCESSORIES

- ERASERS

- EXPRESSION PAPER STUMPS

- FABER CASTELL 9000 PENCILS

- FABER CASTELL ALBRECHT DURER WATERCOLOUR PENCILS

- FABER CASTELL ARTISTS PENCILS

- FABER CASTELL GOLDFABER 1221 PENCILS

- FABER CASTELL PITT CHARCOAL & GRAPHITE

- FABER CASTELL PITT PASTEL STICKS

- FABER CASTELL POLYCHROMOS ARTISTS COLOUR PENCILS

- FABER CASTELL RED RANGE CLASSIC PENCIL SETS

- FABER CASTELL UNIVERSAL MARKING PENCILS

- GENERALS CHARCOAL PENCILS

- HONEYSTICKS BEESWAX CRAYONS

- ICON PENCILS

- JOLLY X-BIG SUPERSTICK PENCILS

- LAMY COLOUR PENCIL SETS

- MECHANICAL PENCILS

- MOLESKINE PENCILS

- MUNGYO WATERCOLOUR CRAYONS

- PENCIL CASES & WRAPS

- PRISMACOLOR PENCILS

- SHARPENERS

- STAEDTLER COLOUR PENCIL SETS

- STAEDTLER CRAYON & PASTEL SETS

- STAEDTLER DESIGN JOURNEY COLOUR PENCIL SETS

- STAEDTLER LUMOCOLOR PENCILS

- STAEDTLER LUNA PENCILS

- STAEDTLER MARS LEADS

- STAEDTLER MARS LUMOGRAPH PENCILS

- STAEDTLER NORIS,NORICA PENCILS

- STAEDTLER TRADITION PENCILS

- TOMBOW MONO GRAPHITE PENCILS

- WOLFF CARBON PENCILS

- PIGMENTS & MEDIUMS

- PRINTER PAPERS, FILMS & LABELS

-

PRINTMAKING

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Clearance

- BLOCK PRINTING KITS

- CHARBONNEL ETCHING GROUNDS

- ESSDEE SCRAPERBOARD

- GELLI PRINTING PLATES

- JACQUARD CYANOTYPE

- JACQUARD SOLARFAST

- PRINTING PLATES, BLOCKS & LINO

- PRINTING PRESSES

-

PRINTMAKING INKS

- AKUA INTAGLIO INK

- AKUA INTAGLIO MEDIUMS

- CHARBONNEL ETCHING INKS

- CHARBONNEL WATER WASHABLE INK

- CHARBONNEL WATER WASHABLE MEDIUMS

- CRANFIELD CALIGO SAFE WASH ETCHING INKS

- CRANFIELD CALIGO SAFE WASH RELIEF INK

- CRANFIELD PRINTMAKING MEDIUMS

- CRANFIELD TRADITIONAL ETCHING INKS

- CRANFIELD TRADITIONAL RELIEF INKS

- ESSDEE FABRIC PRINTING INKS

- ESSDEE WATERBASED BLOCK PRINTING INKS

- FIVE STAR PRINTING INK

- FLINT OIL BASED PRINTING INK

- FLINT WATER BASED PRINTING INK

- SCHMINCKE AQUA LINOPRINT INKS

- SCHMINCKE LINOPRINT MEDIUMS

- SCHMINCKE LINOPRINT SETS

- SPEEDBALL FABRIC RELIEF INKS

- SPEEDBALL PROFESSIONAL RELIEF INKS

- SPEEDBALL WATERBASED RELIEF INKS

-

PRINTMAKING ROLLERS, CUTTERS & TOOLS

- BARENS

- BENCH HOOKS

- ESSDEE COLD WAX ROLLERS

- ESSDEE FABRIC INK ROLLERS

- ESSDEE HARD RUBBER INK ROLLERS

- ESSDEE PROFESSIONAL INK ROLLERS

- ESSDEE SOFT RUBBER INK ROLLERS

- ETCHING NEEDLES

- EXPRESSION STANDARD RUBBER INK ROLLERS

- HWAHONG ROLLERS & TOOLS

- LINO & WOOD CUTTERS & CARVING TOOLS

- SPEEDBALL LINO ROLLERS

- PRINTMAKING STENCILS

- PROJECTORS

- SCHOOL & UNIVERSITY KITS

- SCREENPRINTING

-

SKETCH BOOKS, NOTEBOOKS, VISUAL DIARIES

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Featured

- Clearance

- CRESCENT RENDR SKETCHBOOKS

- FABRIANO ECOQUA NOTEBOOKS

- FABRIANO ISPIRA NOTEBOOKS

- FABRIANO SKETCH & WATERCOLOUR BOOKS

- FLEXBOOK SKETCHBOOKS & NOTEBOOKS

- GORDON HARRIS VISUAL DIARIES

-

HAHNEMUHLE SKETCH BOOKS

- HAHNEMUHLE CAPPUCINO BOOK

- HAHNEMUHLE NOSTALGIE SKETCH BOOK

- HAHNEMUHLE SKETCH BOOK D&S

- HAHNEMUHLE SKETCH BOOK HARDCOVER

- HAHNEMUHLE SKETCH BOOKLETS

- HAHNEMUHLE SPIRAL BOUND SKETCH BOOKS

- HAHNEMUHLE THE GREY BOOK

- HAHNEMUHLE TONED WATERCOLOUR BOOKS

- HAHNEMUHLE TRAVEL JOURNALS

- HAHNEMUHLE WATERCOLOUR BOOKS

- HAHNEMUHLE ZIG ZAG BOOK

- LEUCHTTURM 1917 NOTEBOOKS

- MOLESKINE NOTEBOOKS

- MOLOTOW MARKER SKETCHBOOK

- PAPERBLANKS NOTEBOOKS

- SPECIALTY PAINTS & FINISHES

- SPRAY PAINT

- STATIONERY

-

TAPES, GLUES & ADHESIVES

- Specials

- Clearance

- ADHESIVE PUTTIES & CEMENTS

- ARTOGRAPH SPRAY BOOTHS

- CELLULOSE & INVISIBLE TAPES

- DOUBLE SIDED TAPES & SHEETS

- GLUE GUNS & STICKS

- GLUE STICKS & ROLLERS

- HOLDFAST HOOK & LOOP

- MASKING TAPES & FILMS

- PACKAGING TAPE

- PAPER & CLOTH TAPES

- PVA & WOOD GLUES

- SELF ADHESIVE SHEETS & ROLLS

- SPECIALITY & ALL PURPOSE GLUES

- SPRAY ADHESIVES

- XYRON PROFESSIONAL

- TECHNICAL DRAWING PRODUCTS

- TRACING PAPER & DRAFTING FILM

-

WATERCOLOUR PAINTS & MEDIUMS

- Specials

- New Arrivals

- Clearance

- DANIEL SMITH WATERCOLOUR

- PEBEO WATERCOLOUR MEDIUMS

- PEBEO WATERCOLOUR PAINT SETS

- QOR WATERCOLOURS

- SCHMINCKE AKADEMIE WATERCOLOUR

- SCHMINCKE AQUA DROP

- SCHMINCKE HORADAM WATERCOLOUR

- SCHMINCKE LIQUID CHARCOAL

- SCHMINCKE WATERCOLOUR MEDIUMS

- WATERBRUSH PENS

- WATERCOLOUR STUDENT PAINT SETS

- WINSOR & NEWTON COTMAN WATERCOLOURS

- WINSOR & NEWTON PROFESSIONAL WATERCOLOUR

- WINSOR & NEWTON WATERCOLOUR MARKERS

- WINSOR & NEWTON WATERCOLOUR MEDIUMS

How Artists' Brushes are made

By Evan Woodruffe

I like mixing business and pleasure – it shows us the working side of a culture as well as the tourist attractions. The town of Nuremberg in Germany is a postcard medieval town sitting on the cross roads of east-west and north-south European trading routes, making it a centre for traditional skills like brush-making and gold-beating for centuries. So as well as seeing the amazing Renaissance art in the old city, I wanted to visit my friends at da Vinci Defet, brush-makers par excellence.

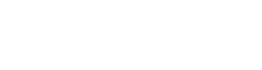

Hairs are agitated in a brass cup to sort the length (left), then short hairs are then pulled from the bundle by hand (middle), and the hair is portioned out (right), depending on the size of the brush.

I was amazed that over 10,000 fine artists’ brushes are made by hand here every day. This is not some sweat shop, however. The silence of concentration from a couple of dozen brush-makers is interrupted occasionally by the gentle hum of agitators and the tapping of brass cases on the marble work benches, a beat somewhere between Dixieland and marching music! I was not so surprised to learn that to become a Master Brush-maker (yes, there is a school in Nuremberg for this) takes longer than studying for a MFA.

How do they sort hair that is upside-down and round-about? Lay them out, rub them with a stick of wood – this simple method separates them into rightside-up and upside-down piles, because sable hair has a “belly” in the middle. And I always thought they sorted it hair by hair…

Although synthetic technology since the 1960s has supplied reliable & inexpensive brushes for many painting techniques, natural hair brushes still out-perform them in some applications and remain important tools for the serious artist. These hairs have been used in Western painting at least since the Renaissance, and come from Siberia and northern China, where the extreme winters produce sturdy hair in the sables (a type of ferret) and black squirrels.

Natural hair brushes must be made by hand. The hair is too fine, and the static charge that builds up in it is unsuitable for machines. Many hog-bristle and synthetic brushes are also made by hand, depending on the type and shape. Many shapes must be hand-made – extra fine pointed brushes, dagger stripers and filberts, for instance; one reason why these shapes are more expensive than flat brushes – they take longer to make.

A sack of sable tails in the vault. There are different qualities of sable – in the middle image, red sable on the left is quite different (and much cheaper) than Kolinsky sable from the male winter coat on the right. The difference is the length of hair, all important to the serious watercolour or oil painter.

There are different qualities of natural hair. The most expensive and valuable soft brush hair comes from the male winter tail of the sable mustela sibirica and is called Tobolsky or Kolinsky after the Siberian river valleys. Hair of other species of sable, such as Asiatic weasel, or the female animals, is not as fine & springy so sells for about half the price. Unfortunately, the purity regulations are abused more and more, and some call this second-grade hair “Kolinsky”, but the difference is soon realised by the artist!

Black sable has been an important to oilpainters since the 19th Century, prized for its ability to blend and layer wet oilcolour. These tails have to be prepared by specialist tanners before becoming sorted bundles of hair, ready to be made into brushes. Each tail may only yield a gram and a half of suitable hair!

While natural hair and high-quality bristle brushes are hand-made, many more brushes are made using semi-automated production. Some early machines were developed for easy jobs like fitting handles, but very high-tech machines, specially designed and made by da Vinci, produce over 3 million mainly synthetic fibre brushes a year. I was not allowed to photograph these unique machines, but can tell you it was fascinating watching the renowned German manufacturing brilliance in action!

Da Vinci invest a lot of time and money into developing new fibres, not only to replace expensive natural resources, but also to suit new styles of painting. Their unique blended fibre technology produces synthetic brushes that hold far more fluid than standard synthetics, making them particularly suited to fluid acrylic techniques, ink and varnish applications, and as economical watercolour brushes.

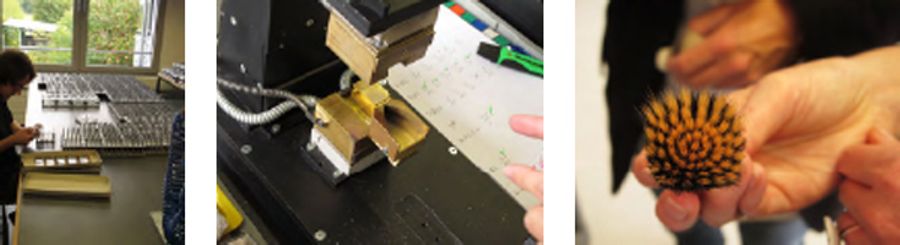

Specially designed jigs (left) make these mottlers quicker to put together, but they’re still all made by hand! Maesto-2 filberts are shaped using special hot irons (middle). Many crazy brushes can be made when you have the experience! This one on the right is a cosmetic brush, but uses a similar technique to the da Vinci Vario-Tip brushes.

Now there are new fibres on the near horizon, as da Vinci develops special synthetic fibres that mimic as close as possible the natural hairs. They wanted my opinion on a couple of these prototype brushes they were testing; one of which performed so closely to squirrel, even the way it floated open in water, that it completely fooled me. I needn’t feel bad – it also fooled a brush-maker of 20 years experience! Another was so fresh, they hurriedly fixed a handle to it so I could take home with me to try in my studio. I can’t reveal too much about this one, except to say it works really, really well.

A push-me pull-you brush (left) made from human hair – these Germans are crazy! The middle brush was made in a café while the owner of da Vinci was talking to an artist, who cut some of his hair and attached it to a pencil with the foil off his cigarette packet! But no matter what brush, they usually end up like these on the right – used for colourful creations and ending up much loved.

Handy Brush Tip – dealing with frizzy brushes

We often get asked about frizzy brushes. Often this is due to scumbling (or dry-brushing) with synthetic brushes, which just won’t cope. Hog hair brushes are better suited to this. However, after washing, hog hair brushes tend to “fluff open”. Here's an old tip for dealing with both kinds of frizzy brushes:

To deal with hog hair brushes, give them a thorough cleaning using da Vinci brush cleaning soap (which will condition as well as clean), paying special attention to where the hair meets the ferrule, shape the brush and tie a thin strip of cotton round the brush head. Thin ribbon is ideal. This will ensure it dries in shape.

For synthetic brushes, after cleaning, one can steam the hair over a boiling kettle or dip the brush head into just boiled water for several minutes before tying it in shape in the method above. Watch your fingers, children! Make sure it’s just the synthetic hair that is in contact with the water, not the metal ferrule, as otherwise you can ruin the brush.

Remember: the only way to save money on good brushes is to look after them. Don’t leave them in water, and always promptly clean using da Vinci brush-cleaning soap – it’s magic!

You can be firm with your brush on the soap as long as you massage the lather from the ferrule to the tip. Use your fingernails to clean paint from around the ferrule. After thoroughly rinsing the soap from the brush head, make sure they dry in shape by giving them Rambo headbands!